Frobenius theorem (differential topology)

In mathematics, Frobenius' theorem gives necessary and sufficient conditions for finding a maximal set of independent solutions of an overdetermined system of first-order homogeneous linear partial differential equations. In modern geometric terms, the theorem gives necessary and sufficient conditions for the existence of a foliation by maximal integral manifolds each of whose tangent bundles are spanned by a given family of vector fields (satisfying an integrability condition) in much the same way as an integral curve may be assigned to a single vector field. The theorem is foundational in differential topology and calculus on manifolds.

Contents |

Introduction

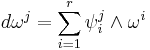

In its most elementary form, the theorem addresses the problem of finding a maximal set of independent solutions of a regular system of first-order linear homogeneous partial differential equations. Suppose that fki(x) are a collection of real-valued C1 functions on Rn, for i = 1, 2, ..., n, and k = 1, 2, ..., r, where r < n, such that the matrix (fki) has rank r. Consider the following system of partial differential equations for a real-valued C2 function u on Rn:

(1)

(1)

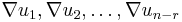

One seeks conditions on the existence of a collection of solutions u1, ..., un−r such that the gradients

are linearly independent.

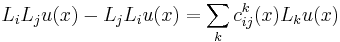

The Frobenius theorem asserts that this problem admits a solution locally[1] if, and only if, the operators Lk satisfy a certain integrability condition known as involutivity. Specifically, they must satisfy relations of the form

for i, j = 1, 2,..., r, and all C2 functions u, and for some coefficients ckij(x) that are allowed to depend on x. In other words, the commutators [Li,Lj] must lie in the linear span of the Lk at every point. The involutivity condition is a generalization of the commutativity of partial derivatives. In fact, the strategy of proof of the Frobenius theorem is to form linear combinations among the operators Li so that the resulting operators do commute, and then to show that there is a coordinate system yi for which these are precisely the partial derivatives with respect to y1, ..., yr.

From analysis to geometry

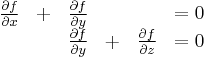

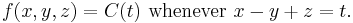

Solutions to underdetermined systems of equations are seldom unique. For example, the system

clearly lacks a unique solution. Nevertheless, the solutions still have enough structure that they may be completely described. The first observation is that, even if f1 and f2 are two different solutions, the level surfaces of f1 and f2 must overlap. In fact, the level surfaces for this system are all planes in R3 of the form x − y + z = C, for C a constant. The second observation is that, once the level surfaces are known, all solutions can then be given in terms of an arbitrary function. Since the value of a solution f on a level surface is constant by definition, define a function C(t) by:

Conversely, if a function C(t) is given, then each function f given by this expression is a solution of the original equation. Thus, because of the existence of a family of level surfaces, solutions of the original equation are in a one-to-one correspondence with arbitrary functions of one variable.

Frobenius' theorem allows one to establish a similar such correspondence for the more general case of solutions of (1). Suppose that u1,...,un−r are solutions of the problem (1) satisfying the independence condition on the gradients. Consider the level sets[2] of (u1,...,un-r) regarded as an Rn−r-valued function. If v1,...,vn−r is any other such collection of solutions, one can show (using some linear algebra and the mean value theorem) that this has the same family of level sets as the u's, but with a possibly different choice of constants for each set. Thus, even though the independent solutions of (1) are not unique, the equation (1) nonetheless determines a unique family of level sets. Just as in the case of the example, general solutions u of (1) are in a one-to-one correspondence with (continuously differentiable) functions on the family of level sets.[3]

The level sets corresponding to the maximal independent solution sets of (1) are called the integral manifolds because functions on the collection of all integral manifolds correspond in some sense to "constants" of integration. Once one of these "constants" of integration is known, then the corresponding solution is also known.

Frobenius' theorem in modern language

The Frobenius theorem can be restated more economically in modern language. Frobenius' original version of the theorem was stated in terms of Pfaffian systems, which today can be translated into the language of differential forms. An alternative formulation, which is somewhat more intuitive, uses vector fields.

Formulation using vector fields

In the vector field formulation, the theorem states that a subbundle of the tangent bundle of a manifold is integrable (or involutive) if and only if it arises from a regular foliation. In this context, the Frobenius theorem relates integrability to foliation; to state the theorem, both concepts must be clearly defined.

One begins by noting that an arbitrary smooth vector field X on a manifold M can be integrated to define a family of curves. The integrability follows because the equation defining the curve is a first-order ordinary differential equation, and thus its integrability is guaranteed by the Picard–Lindelöf theorem. Indeed, vector fields are often defined to be the derivatives of a collection of smooth curves.

This idea of integrability can be extended to collections of vector fields as well. One says that a subbundle  of the tangent bundle TM is integrable (or involutive), if, for any two vector fields X and Y taking values in E, then the Lie bracket

of the tangent bundle TM is integrable (or involutive), if, for any two vector fields X and Y taking values in E, then the Lie bracket ![[X,Y]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/ab4fc7097880a47a3c8db15b20f8ff3d.png) takes values in E as well. This notion of integrability need only be defined locally; that is, the existence of the vector fields X and Y and their integrability need only be defined on subsets of M.

takes values in E as well. This notion of integrability need only be defined locally; that is, the existence of the vector fields X and Y and their integrability need only be defined on subsets of M.

A subbundle  may also be defined to arise from a foliation of a manifold. Let

may also be defined to arise from a foliation of a manifold. Let  be a submanifold that is a leaf of a foliation. Consider the tangent bundle TN. If TN is exactly E restricted to N, then one says that E arises from a regular foliation of M. Again, this definition is purely local: the foliation is defined only on charts.

be a submanifold that is a leaf of a foliation. Consider the tangent bundle TN. If TN is exactly E restricted to N, then one says that E arises from a regular foliation of M. Again, this definition is purely local: the foliation is defined only on charts.

Given the above definitions, Frobenius' theorem states that a subbundle E is integrable if and only if it arises from a regular foliation of M.

Differential forms formulation

Let U be an open set in a manifold M, Ω1(U) be the space of smooth, differentiable 1-forms on U, and F be a submodule of Ω1(U) of rank r, the rank being constant in value over U. The Frobenius theorem states that F is integrable if and only if for every  the stalk Fp is generated by r exact differential forms.

the stalk Fp is generated by r exact differential forms.

Geometrically, the theorem states that an integrable module of 1-forms of rank r is the same thing as a codimension-r foliation. The correspondence to the definition in terms of vector fields given in the introduction follows from the close relationship between differential forms and Lie derivatives. Frobenius' theorem is one of the basic tools for the study of vector fields and foliations.

There are thus two forms of the theorem: one which operates with distributions, that is smooth subbundles D of the tangent bundle TM; and the other which operates with subbundles of the graded ring Ω(M) of all forms on M. These two forms are related by duality. If D is a smooth tangent distribution on M, then the annihilator of D, I(D) consists of all forms α ∈ Ω(M) such that

for all v ∈ D, where i denotes the interior product of a vector field with a k-form. The set I(D) forms a subring and, in fact, an ideal in Ω(M). Furthermore, using the definition of the exterior derivative, it can be shown that I(D) is closed under exterior differentiation (it is a differential ideal) if and only if D is involutive. Consequently, the Frobenius theorem takes on the equivalent form that I(D) is closed under exterior differentiation if and only if D is integrable.

Generalizations

The theorem may be generalized in a variety of ways.

Infinite dimensions

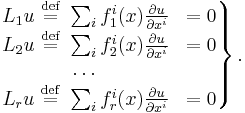

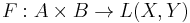

One infinite-dimensional generalization is as follows.[4] Let X and Y be Banach spaces, and A ⊂ X, B ⊂ Y a pair of open sets. Let

be a continuously differentiable function of the Cartesian product (which inherits a differentiable structure from its inclusion into X×Y) into the space L(X,Y) of continuous linear transformations of X into Y. A differentiable mapping u : A → B is a solution of the differential equation

(1)

(1)

if u′(x) = F(x,u(x)) for all x ∈ A.

The equation (1) is completely integrable if for each  , there is a neighborhood U of x0 such that (1) has a unique solution u(x) defined on U such that u(x0)=y0.

, there is a neighborhood U of x0 such that (1) has a unique solution u(x) defined on U such that u(x0)=y0.

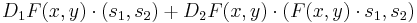

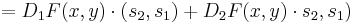

The conditions of the Frobenius theorem depend on whether the groundfield is R or C. If it is R, then assume F is continuously differentiable. If it is C, then assume F is twice continuously differentiable. Then (1) is completely integrable at each point of A×B if and only if

for all s1, s2 ∈ X. Here the dot product denotes the action of the linear operator F(x,y) ∈ L(X,Y), as well as the action of the operator D1(x,y) ∈ L(X,L(X,Y)) and D2(x,y) ∈ L(Y, L(X,Y)).

Banach manifolds

The infinite dimensional version of the Frobenius theorem also holds on Banach manifolds.[5] The statement is essentially the same as the finite dimensional version.

Let M be a Banach manifold of class at least C2. Let E be a subbundle of the tangent bundle of M. The bundle E is involutive if, for each point p ∈ M and pair of sections X and Y of E defined in a neighborhood of p, the Lie bracket of X and Y evaluated at p lies in Ep:

On the other hand, E is integrable if, for each p ∈ M, there is an immersed submanifold φ : N → M whose image contains p, such that the differential of φ is an isomorphism of TN with φ-1E.

The Frobenius theorem states that a subbundle E is integrable if and only if it is involutive.

Holomorphic forms

The statement of the theorem remains true for holomorphic 1-forms on complex manifolds — manifolds over C with biholomorphic transition functions.[6]

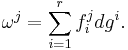

Specifically, if  are r linearly independent holomorphic 1-forms on an open set in Cn such that

are r linearly independent holomorphic 1-forms on an open set in Cn such that

for some system of holomorphic 1-forms ψij, i,j=1,...,r, then there exist holomorphic functions fij and gi such that, on a possibly smaller domain,

This result holds locally in the same sense as the other versions of the Frobenius theorem. In particular, the fact that it has been stated for domains in Cn is not restrictive.

Higher degree forms

The statement does not generalize to higher degree forms, although there are a number of partial results such as Darboux's theorem and the Cartan-Kähler theorem.

History

Despite being named for Ferdinand Georg Frobenius, the theorem was first proven by Alfred Clebsch and Feodor Deahna. Deahna was the first to establish the sufficient conditions for the theorem, and Clebsch developed the necessary conditions. Frobenius is responsible for applying the theorem to Pfaffian systems, thus paving the way for its usage in differential topology.

See also

Notes

- ^ Here locally means inside small enough open subsets of Rn. Henceforth, when we speak of a solution, we mean a local solution.

- ^ A level set is a subset of Rn corresponding to the locus of:

- (u1,...,un-r) = (c1,...,cn−r),

- ^ The notion of a continuously differentiable function on a family of level sets can be made rigorous by means of the implicit function theorem.

- ^ Dieudonné, J (1969). Foundations of modern analysis. Academic Press. Chapter 10.9.

- ^ Lang, S. (1995). Differential and Riemannian manifolds. Springer-Verlag. Chapter VI: The theorem of Frobenius. ISBN 978-0387943381.

- ^ Kobayashi, Shoshichi and Nomizu, Katsumi (1969). Foundations of Differential Geometry, Vol. 2. Wiley-Interscience. Appendix 8.

References

- H. B. Lawson, The Qualitative Theory of Foliations, (1977) American Mathematical Society CBMS Series volume 27, AMS, Providence RI.

- Ralph Abraham and Jerrold E. Marsden, Foundations of Mechanics, (1978) Benjamin-Cummings, London ISBN 0-8053-0102-X See theorem 2.2.26.

- Clebsch, A. "Ueber die simultane Integration linearer partieller Differentialgleichungen", J. Reine. Angew. Math. (Crelle) 65 (1866) 257-268.

- Deahna, F. "Über die Bedingungen der Integrabilitat ....", J. Reine Angew. Math. 20 (1840) 340-350.

- Frobenius, G. "Über das Pfaffsche probleme", J. für Reine und Agnew. Math., 82 (1877) 230-315.

![[X,Y]_p \in E_p](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/5fa54bc8fff9f6e0c3f6a39e6e0bd734.png)